Key Takeaways

- The Federal Reserve is pumping the breaks on the economy to help combat inflation. But has it already induced a recession? The great debate is on.

- “Recession” is traditionally defined as two consecutive quarters of negative growth. However, it’s important to remember that the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) is the entity responsible for making the ultimate determination, using an array of data points such as employment, personal income, industrial production and more.

- Despite the negative GDP prints of the past two quarters, consumer spending, business investment and the current state of the labor market are not currently signaling recession. However, the situation is dynamic and we’re watching the Fed to see if it can orchestrate a soft landing.

Also included are the following themes:

Economic Vista: The (recession) debate rages

One of the hottest debates in the court of public opinion over the past several weeks has not been whether Top Gun Maverick was better than the original, but rather if we really are in a recession. After a negative first-quarter gross domestic product (GDP) reading, the debate began on “what if” we get a negative reading in the second quarter. Then, in July, GDP fell by an annualized rate of 0.9%, according to the advance estimate from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA).

The widely accepted “technical” definition of recession is two consecutive quarters of economic contraction. So, does that mean it’s official? Well, not exactly. After all, it’s the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) that is responsible for making that determination. In doing so, the NBER considers a variety of data besides GDP—labor market statistics, personal income and industrial production, to name a few — before officially declaring a recession.

Before we wade into the debate, let’s first define GDP — the most common measure of economic growth. According to the BEA, GDP measures the value of the final goods and services produced in the United States (without double-counting the intermediate goods and services used to produce them). Let’s also review the GDP calculation formula (nerd alert!): GDP = C + I + G + (X-M). To spell it out: GDP = private consumption + gross private investment + government spending + (exports – imports).

One other important note regarding GDP readings: For each quarter, there are a total of three readings from the BEA. The first two are preliminary readings that get revised at a later date, while the third “final” reading trickles in months later. The BEA also conducts annual updates, so the numbers can and do bounce around — sometimes unexpectedly. That’s just the nature of the data.

In contrast to the more traditional definition, the NBER defines recession as a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and lasts more than a few months. The committee’s view is that while each of the three criteria — depth, diffusion and duration — needs to be met individually to some degree, extreme conditions revealed by one criterion may partially offset weaker indications from another. For example, in 2001, the recession did not include two consecutive quarters of decline in real GDP, but the NBER called it a recession nonetheless. With all the revisions and sorting through of data, it typically takes the NBER at least four to six months to determine if a recession has started.

What does all this suggest for 2022 economic growth? Although the first-quarter GDP reading was negative, demand was very solid, with most of the negative reading being attributable to large imports —a commodity that is subtracted when calculating GDP. In addition, business investment was up 10% — not what one would normally consider recessionary.

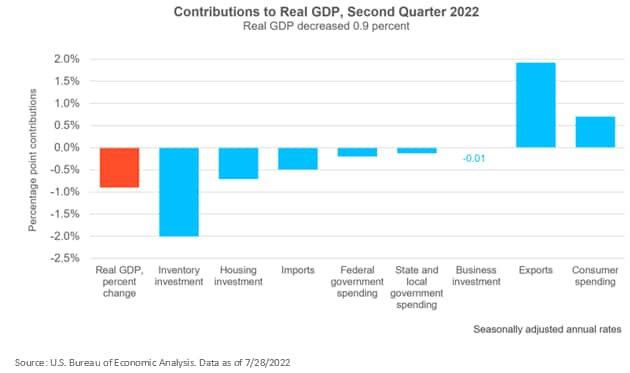

Fast forward to July and we get the first reading of second-quarter GDP. Market consensus called for a +0.4% reading, while the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s GDPNow forecasting model predicted a contraction of -1.2%. The actual reading came in at -0.9%. The main contributor to the negative reading was a large decline in the pace of inventory growth as businesses drew down from existing stockpiles. This alone subtracted two percentage points from GDP. So, if you exclude the impact of inventories, real GDP would have been positive. Although personal consumption came in at 1.0%, which is the lowest reading since the onset of COVID-19, the low reading was likely due to grocery spending and higher food prices. The accompanying graph shows all the contributions to second-quarter GDP in greater detail.

One of the most interesting aspects of the recession debate pertains to the labor market. For the first two quarters of 2022, there have been 2.7 million jobs added, and the unemployment rate is close to a 50-year low, hovering around 3.6%. In addition, there are nearly two jobs available for every unemployed worker. Those are not likely to be considered recessionary numbers by the NBER. Furthermore, while industrial production declined in June, that statistic follows five consecutive months of expansion and solid growth of 6.2%, annualized, for the second quarter. Again, this is unlikely to be considered recessionary.

GDP readings are important for their optics, and both Treasury Secretary Yellen and President Biden discussed the latest numbers after the last release. Secretary Yellen noted that a recession is a “broad-based weakening of our economy,” which includes significant layoffs and businesses shutting down, and that’s not what we are seeing right now. “When you look at the economy,” she added, “job creation is continuing, household finances remain strong, consumers are spending and businesses are growing.” President Biden also downplayed the notion that we are in a recession saying, “If you look at our job market, consumer spending [and] business investment, we see signs of economic progress in the second quarter as well.”

So, who wins this debate in the end? We believe that’s yet to be determined. However, I think we would all agree that consumer demand and economic growth have slowed, which is exactly what the Federal Reserve has been striving for in its fight against inflation. This is the Fed’s number-one priority right now, so any cooling of demand is likely to be viewed as good news in the near term. Of course, it’s a fine line and will be interesting to see if the Fed can orchestrate the proverbial soft landing. Despite headlines about the negative GDP print, the economic outlook does not appear too dire —at least for now. However, whether this slowdown morphs into a definitive recession is yet to be seen. We’ll likely have to wait for additional data before the NBER makes it official.

Credit Vista: Taking stress out of the test

Fiona Nguyen, Senior Credit Research Advisor

Second quarter earnings season is well under way and the majority of U.S. banks have just reported. In aggregate, the results were certainly less impressive compared to the record profitability banks raked in last year. As volatility picked up across fixed income and equity markets, deal-making activity plummeted, resulting in a decline in investment banking revenues. Mortgage banking revenues have also slowed, affected by the steep rise in mortgage rates as the Federal Reserve continues to raise interest rates. But it certainly wasn’t all bad news. On the flip side, consecutive Fed rate hikes provided a major boost to banks’ core lending activity, and the net interest income has finally started to fully realize the higher rate benefit. On the expense side, most banks have budgeted higher loan loss provisions, partly to simply account for the pickup in loan demand, and partly due to changes in economic assumptions. This, along with higher operating expenses, dented the bottom line.

Despite the lower profitability, credit sentiment remains constructive for the industry as a whole. There are ample reasons to be optimistic. Heading into this quarter’s earnings, 33 systemically important banks have passed the Fed’s annual stress test. At a time when investors continue to keep a close eye on inflation while also preparing for different recessionary scenarios, the results of the stress test offer a timely reprieve. The Fed concluded that the largest banks would be able to withstand severe economic stress and still maintain strong capital levels, allowing them to support the economy and households during an economic downturn.

The Fed’s stress test is designed to put the largest banks through a series of adverse economic scenarios and to measure their capital strength and solvency. Some of the adverse economic conditions employed in this year’s test were even more pronounced than last year. Under the severely adverse scenario, for example, real GDP would decline more than 3.5% from the fourth quarter of 2021 to its trough in the first quarter of 2023, the unemployment rate would climb to a peak of 10%; CPI inflation would fall from 8.25% to 1.25% (due to rising unemployment, falling demand, and the rapid decline in GDP growth) then gradually increase above 1.5%; commercial real estate prices would decline by 40%; the stock market would drop by 55%; and the corporate bond market would experience significant disruption. In addition, the systematically important banks with large trading operations must also account for global market shocks and counterparty losses.

Good news. Despite these harsh “test” conditions, all the banks stress-tested were able to maintain their capital ratios above the minimum requirements. However, most banks that were tested experienced large declines in stressed capital, and as a result they would most likely need to curb shareholder returns to bolster capital buffers.

While the stress test affords us greater confidence on the overall system’s solvency, we must still be mindful of near-term credit challenges, many of which are tied to the uncertain economic outlook. For example, a prolonged inflationary environment would curtail consumer spending and corporate investments, leading to lower loan demand that could neutralize the higher rate benefit. As a risk-off tone continues to dominate the markets, we continue to take a cautious approach when assessing bank fundamentals. Yet, it is a comfort knowing a crucial cornerstone of the economy has positioned itself adequately to take on any potential economic turmoil in the second half of 2022 and beyond.

Trading Vista: What’s next, Fed?

Hiroshi Ikemoto, Senior Fixed Income Trader

As widely expected, the Fed raised the fed funds target by 75 basis points (bps) at the July meeting, bringing the target range up to 2.25%–2.50%. This move certainly didn’t spook the market and seemed to be baked into traders’ expectations. In fact, July saw an increasing appetite for risk assets. Chairman Powell did not explicitly state the size of the next hike, and there was little change to the Fed’s post-meeting statement. Thus, it looks like we are heading toward a full “data-dependent” approach going forward, though most analysts are still expecting another 100-bps of hikes this year. So now the key question becomes: At what pace will the future rate hikes be implemented?

In the short-term market, demand for reserve repurchase agreements (RRPs) continues to be robust, with participation and size at or near all-time highs. This was evidenced by a record 111 participants utilizing $2.3 trillion in RRPs in July. The Treasury Department pledged to further increase the amount of bills outstanding by $100 billion by the end of the quarter to alleviate all the cash sitting on the sidelines. However, most analysts are suggesting that much more supply needs to be injected into the market to have any impact on the cash glut. That said, the bill market continues to be well-bid for maturities inside six months. Looking at credit in the money market space, commercial paper has provided the highest yields as issuers continue to fill their funding needs. Rates on high-quality banks in the six- to 12-month space have been 50 to 75-bps higher than like-maturing Treasuries.

Demand for investment-grade corporate bonds remains strong, with tightening spreads and efficient trading. Looking at the curve further out, the two-year US Treasury benchmark note yield — the most sensitive to monetary policy — oscillated from 2.82% to 3.24% in July as volatility continued after every data print and Fed speech.

In the coming weeks and months, the market is likely to respond more immediately to Fed speeches than it typically does to market data, which is backward-looking by nature. Any hints related to inflation, recession or shifts in the workforce will likely trigger rate volatility. An example of this occurred on August 2, 2022, when multiple Fed officials were out in force suggesting that a 75-bps tightening was still on the table with no hints of pauses. The two-year note immediately sold off, and the yield increased 18 bps. This type of reaction, along with future economic indicators, will dictate the shape of the yield curve and provide opportunities to invest our portfolios opportunistically.

Markets |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Treasury Rates: | Total Returns: | ||

| 3-Month | 2.32% | ICE BofA 3-Month Treasury | 0.05% |

| 6-Month | 2.84% | ICE BofA 6-Month Treasury | 0.09% |

| 1-Year | 2.89% | ICE BofA 12-Month Treasury | 0.17% |

| 2-Year | 2.88% | S&P 500 | 8.08% |

| 3-Year | 2.81% | Nasdaq | 11.38% |

| 5-Year | 2.68% | ||

| 7-Year | 2.68% | ||

| 10-Year | 2.65% | ||

|

Source: Bloomberg and Silicon Valley Bank as of 07/29/2022. |

|||