- The US fiscal situation has deteriorated, evidenced by the recent credit downgrade, and bond market participants are taking notice.

- Amidst rising Treasury supply and ballooning fiscal deficits, investors are now demanding additional yield premiums to buy Treasuries.

- Despite the concerns, Treasuries are the largest and most liquid bond market in the world, and they remain a safe haven asset with a vital role in most investor portfolios.

Economic vista: Stay vigilant(es)

Steve Johnson, CFA, Senior Portfolio Manager

It’s not uncommon for dire market-related news to drop late on Friday afternoons, usually in hopes that investors might somehow not notice or otherwise care less in front of a summer weekend. That was the case mid-May when Moody’s made a late-Friday announcement that it had downgraded the US government’s credit rating to Aa1 from Aaa. While it was old news compared to S&P’s 2011 or Fitch’s 2023 equivalent downgrades, it was a chilling reminder for market participants that the fiscal health of the US government appears to be deteriorating. So we must ask, does this credit downgrade really matter? Should we be concerned about the current fiscal situation and trajectory? And should this affect how investors structure fixed income portfolios?

To help answer these important questions, we cobbled together a series of interesting graphs and a short analysis that may help investors better understand the current situation.

A borrowing binge

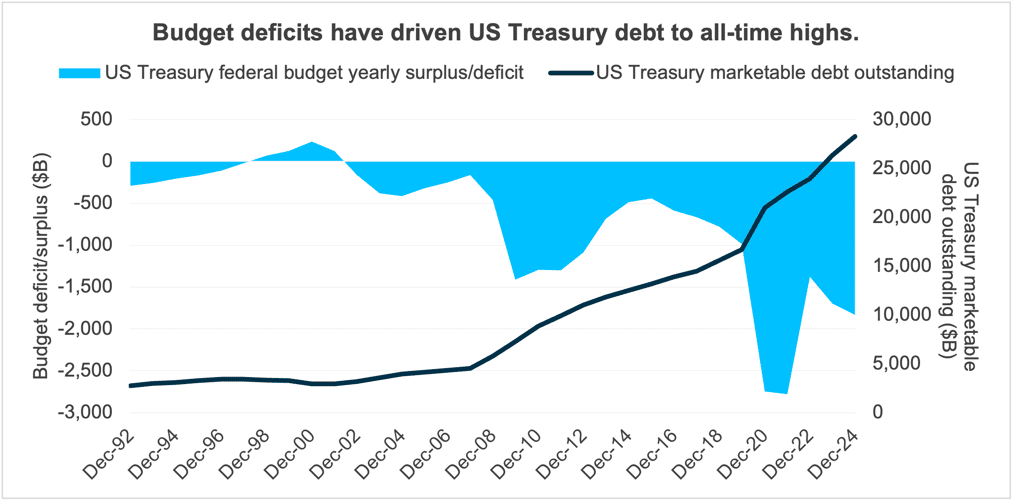

US public debt has skyrocketed over the past decade as federal spending has continued unabated and tax cuts have reduced government revenues. To make up the shortfall, the US Treasury has bridged the budget gap through the continued issuance of Treasury securities. The numbers are large and still growing.

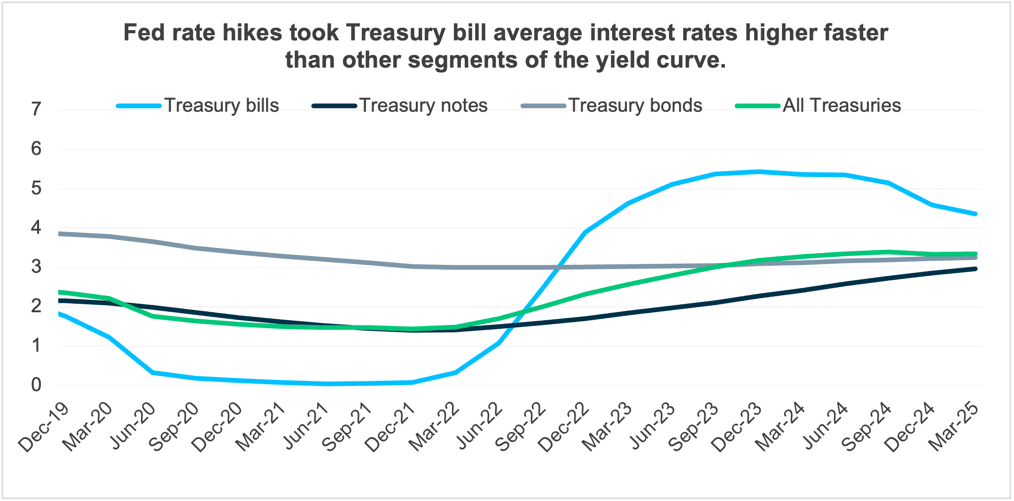

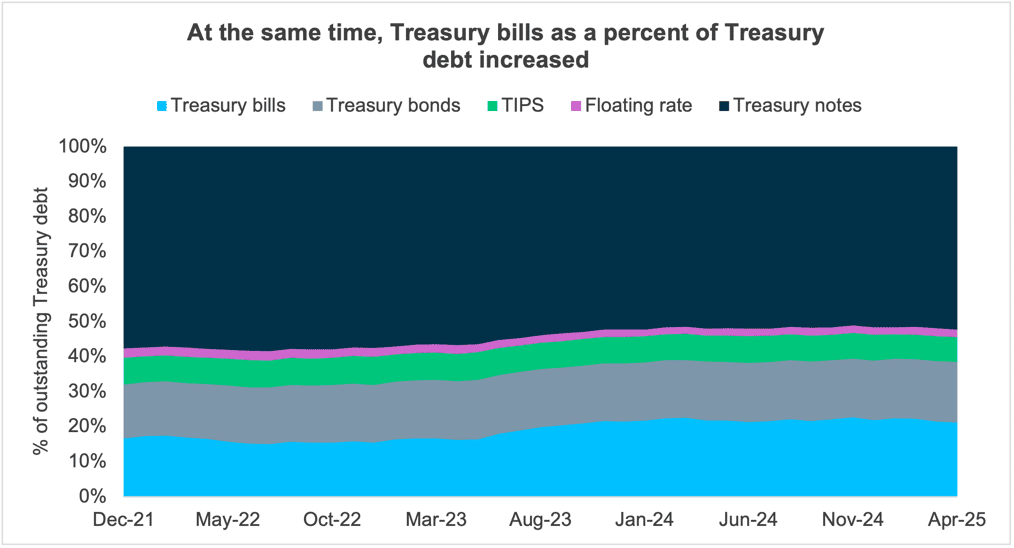

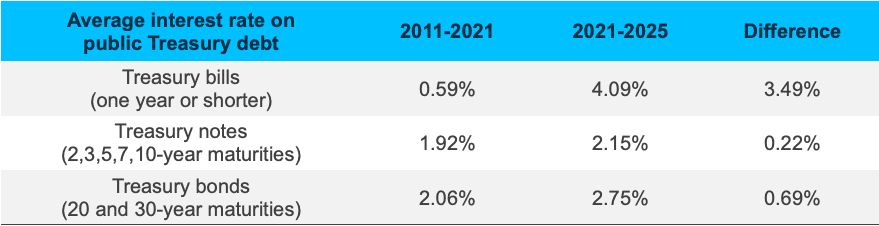

At the same time, the borrowing binge ramped up, and the Fed’s post-COVID-19 war on inflation drove policy rates to a 23-year high. As a result, coupons on more recently auctioned Treasury securities rose to levels not seen in years, especially compared with the 2010s. Treasury securities with shorter maturity dates (like Treasury bills), which frequently roll over and need to be reissued at current interest rates, pushed the average interest rate paid by the US Treasury even higher. To make matters more punitive, Treasury bills as a percentage of Treasury debt outstanding grew steadily in the post-COVID-19 era, as illustrated below.

For example, Treasury bills had an average interest rate of over 4% since 2021, nearly 3.5% higher than in the preceding decade. During that period, Treasury bills rose to 22% of US Treasury debt outstanding by year-end 2024, up from less than 17% at year-end 2021. By comparison, Treasury notes and bonds increased in average yield by significantly less given their longer time to maturity and thus larger proportion of previously issued and (still outstanding) lower-coupon securities.

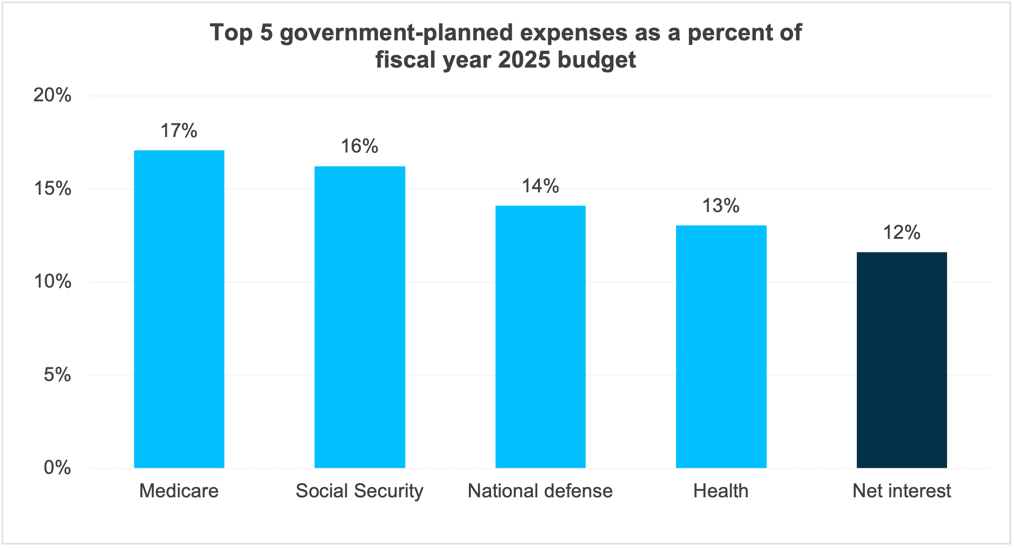

These higher rates may be beneficial for income-seeking investors, but it also means that Uncle Sam is paying out a lot more — in fact, record amounts — of interest expense. In 2025 for example, interest expense is expected to reach over $648 billion, or about 12% of the US government’s overall budget. This colossal expense is expected to trail only Medicare, Social Security, national defense and other health-related outlays1 within the government’s budget. The graph below offers some perspective.

Investors want compensation

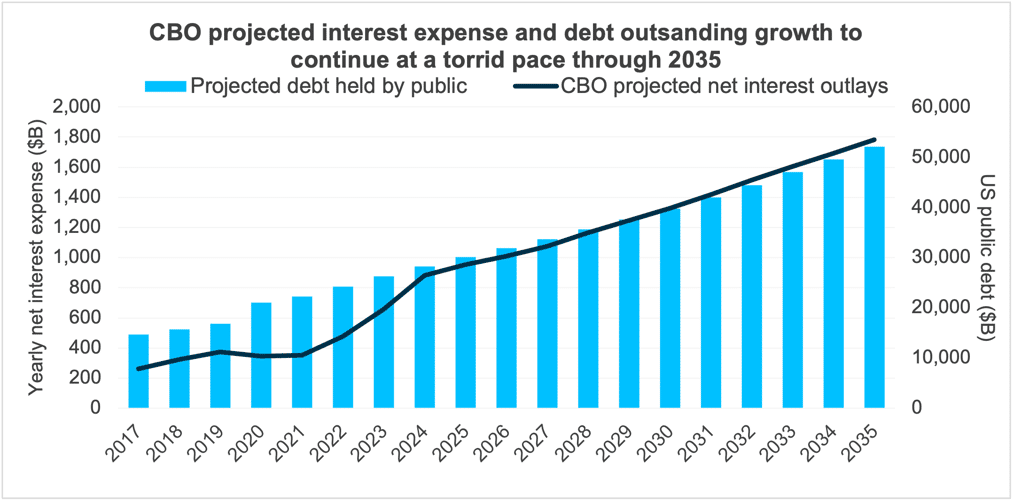

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) — an independent and nonpartisan federal agency — expects annual interest expenses to rise over the next decade to $1.7 trillion by fiscal year 2035.2 This is more than double 2025’s projected interest expense. Public US Treasury marketable debt is expected to skyrocket to over $50 trillion in the same period.

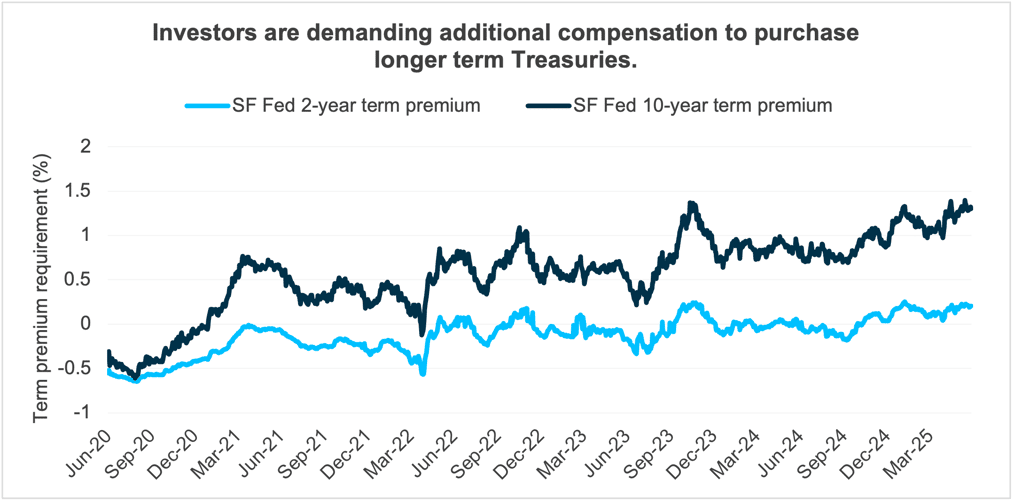

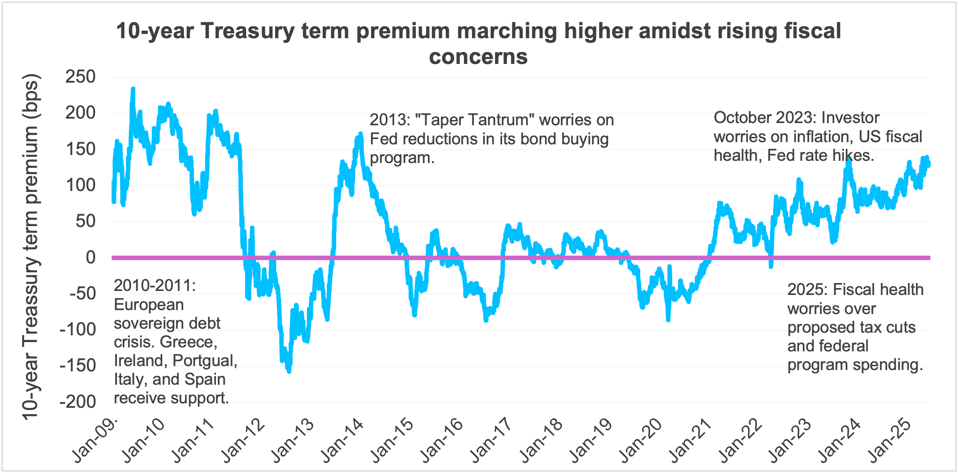

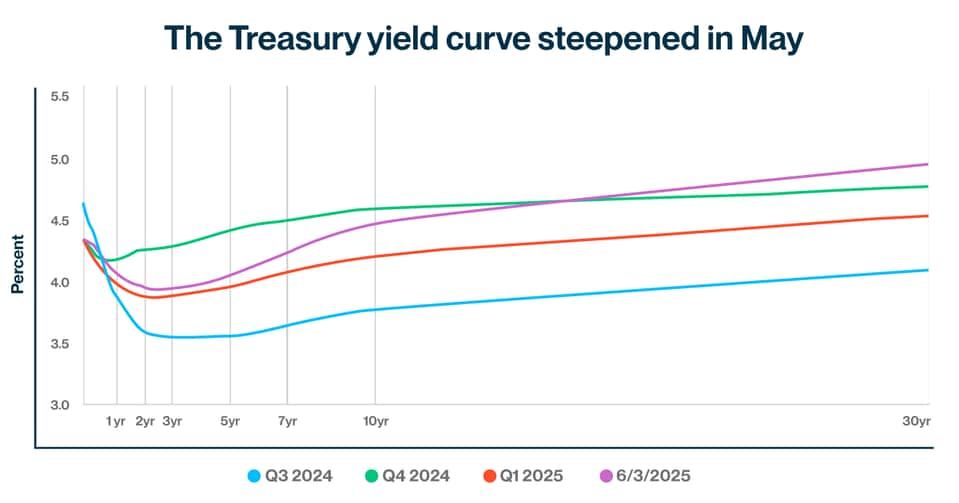

Rating agencies aren’t the only ones taking notice or action. Investors’ requirement for compensation (i.e., yield) to purchase Treasury securities has steadily increased in the post-COVID-19 era. Decomposing nominal Treasury yields into both an average policy rate expectation and an uncertainty premium (known as term premium), we can see that investors today want significantly more compensation to purchase Treasuries. Higher perceived risk begets higher reward. And right now investors want to be paid beyond their expectation for the average Fed policy rate over the respective Treasury security’s lifetime.

For example, in the early days of the pandemic, investors would accept less compensation (negative term premium) to purchase a 2-year or 10-year Treasury, compared with their average expectation for policy rates over the next two or 10 years, respectively. Today, term premium requirements have increased by nearly 70 basis points (bps) for 2-year Treasuries and nearly 160 bps for 10-year Treasuries.3

Still a safe haven

Despite the debt trajectory and recent high-profile credit downgrade, we can unequivocally say that Treasuries maintain their safe-haven status and continue to be a staple in investors’ fixed income portfolios. Treasuries remain a ballast and a means to diversify other parts of investors’ portfolios and are still the most liquid bond market across the world. The US government remains fully capable of funding itself and continuing its pristine track record for repaying principal and interest.

Still, investors are now demanding higher yields than they have in recent years to compensate for rising concerns about fiscal stability. A rising debt pile, surging interest expense and elevated interest rates have investors monitoring the situation carefully. There’s even been more chatter that the greater term premiums today’s investors are demanding represent the return of “bond vigilantes” — those bond market participants who will demand high enough yields to force the government to change course. Bottom line: We certainly don’t believe the current situation is cause for any knee-jerk changes in portfolios. Rest assured, we’re tracking the situation while vigilantly managing fixed income portfolios for our clients.

Credit vista: No AAA, no problem

Timothy Lee, CFA, Senior Credit Analyst

At this point, political brinkmanship and raucous debate surrounding the country’s fiscal deficit and accumulated national debt are nothing more than old news. Some may argue that the recent Moody’s credit downgrade — whereby the US lost its last AAA credit rating in May 2025 — is also old news. After all, the US previously faced credit downgrades in August 2011 and again in 2023 from other ratings agencies. Does this really matter?

Although widening deficits are not a good look, investors should rest assured that Treasuries remain a de facto, risk-free investment. The full faith and credit of the US continues to be backed by the scale of the largest economy in the world with stable institutions, independent monetary policymaking, high productivity driven by technological innovation and control of the world’s preeminent reserve currency. That does not appear to be at risk, from our perspective.

A few facts

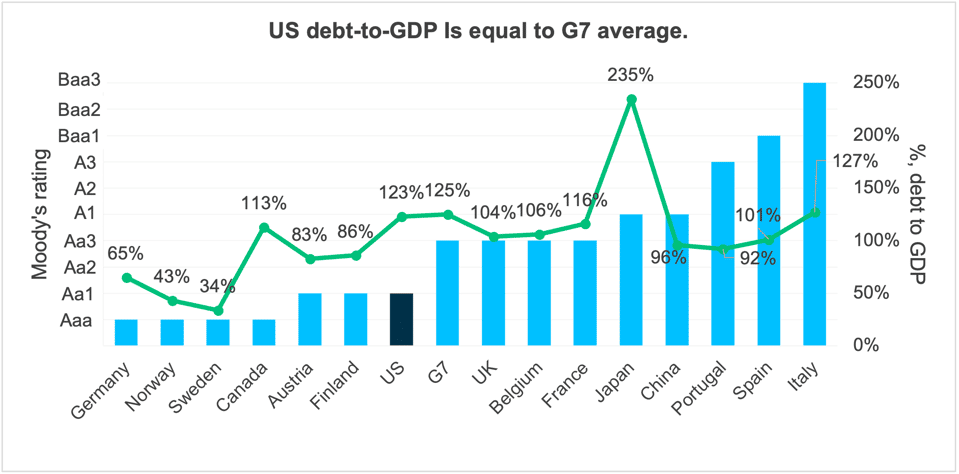

The government’s balance sheet remains secure despite no longer having any AAA rating. The 2025 debt-to-GDP ratio of 123% is near the G7 average of 125% and not far from Aaa-rated Canada’s 113% level. While debt-to-GDP is at least twice as high as other Aaa countries, such as Germany and Norway, the size of the US economy is more than 6x that of Germany and nearly 30x the size of Sweden and Norway’s economies combined. This enormous scale provides significant financial flexibility to address its fiscal health and supports a US credit rating that is two notches higher than the average G7 country rating.

Sovereign vs. corporate debt

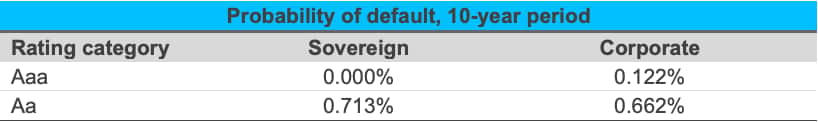

The downgrade of the country’s credit rating to Aa1 by Moody’s implies Aaa-rated companies like Microsoft, Johnson & Johnson and Apple now have lower credit risk. Based on Moody’s ratings performance data, the probability of default for the US over a 10-year period increased from 0% to 0.7%. Comparatively, the probability of default is nearly 0.6% lower at 0.12% for a Aaa-rated corporation.

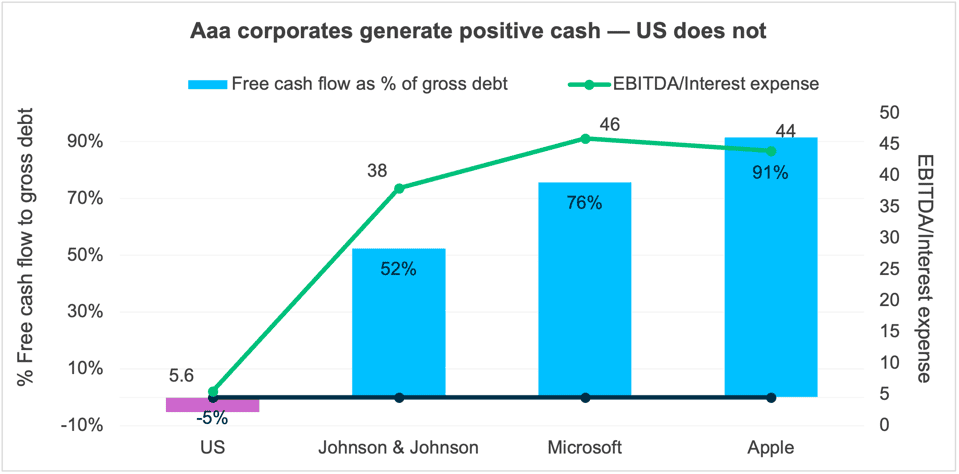

Why this difference? From a credit analyst’s perspective, the Aaa companies have a strong edge over the US government when it comes to cash flow metrics. While the US is generating enough receipts to comfortably cover 5.6x the interest owed on its debt, this multiple pales in comparison to Johnson & Johnson, Microsoft and Apple, which have coverage ratios ranging from 38x to 46x.

The three Aaa companies in this example also generate substantial free operating cash flow in comparison to the amount of debt they carry. Apple’s free cash flow in fiscal year 2024 equaled 91% of its total outstanding debt. At that pace, it would take just a little over a year for Apple to generate enough cash to extinguish all its debt. At Microsoft, free cash flow-to-total debt was 76%, while Johnson & Johnson’s free cash flow generation was equal to 52% of total debt, implying it would take just over two years to produce the cash needed to pay off its outstanding debt. Meanwhile, the US had negative free cash flow4 because of a budget deficit, which required an increase in gross debt to cover all its outlays in fiscal 2024.

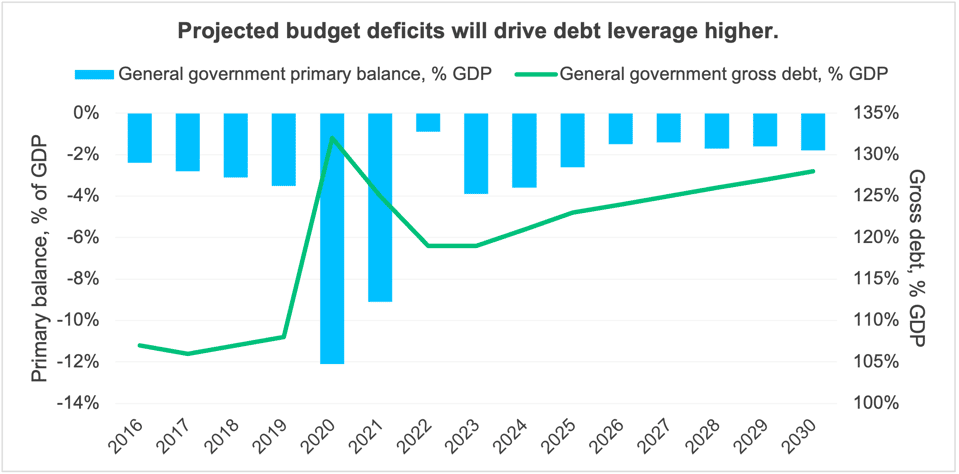

Continued negative cash flow from forecasted budget deficits will be the main driver of growth in US Treasuries outstanding. Higher total borrowings are expected to drive up the US debt-to-GDP ratio from 121% in 2024 to 128% by 2030.

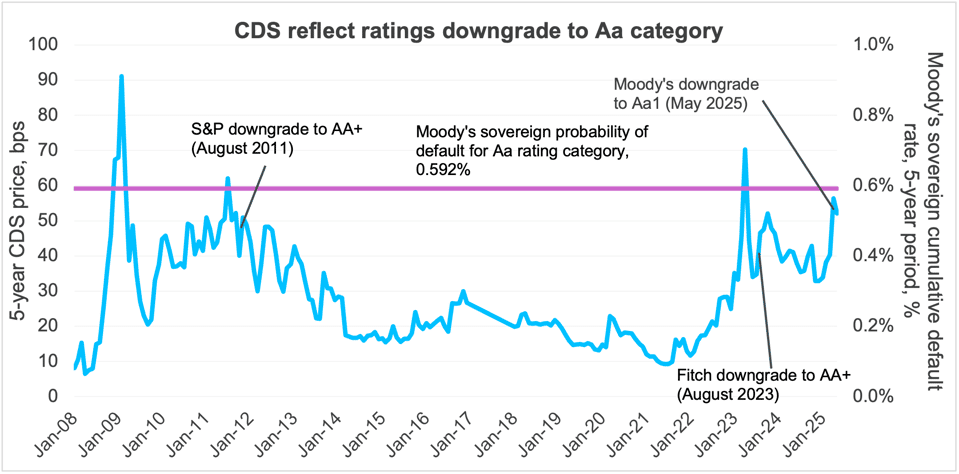

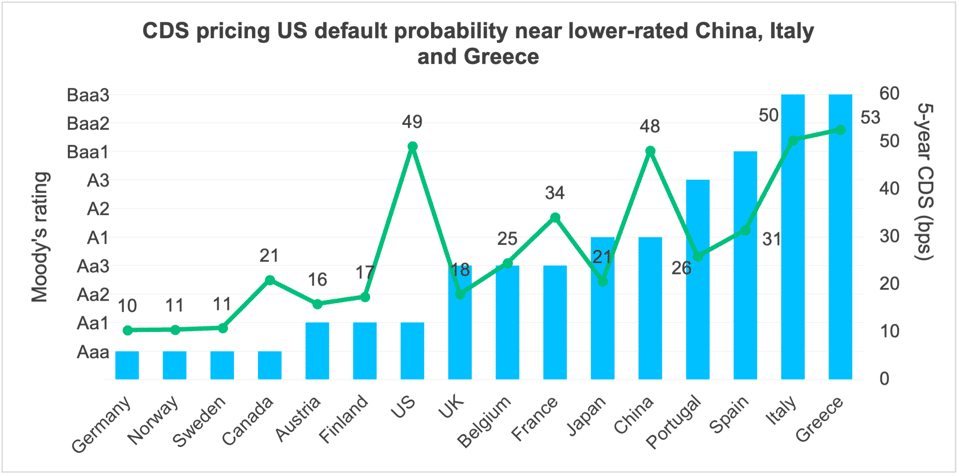

Investors’ attention to deteriorating credit fundamentals for the US was heightened by the recent budget battles in Congress, as well as the headlines regarding the recent credit downgrade in May 2025. But it’s important to keep perspective. Reaction in the credit default swaps (CDS) market looks awfully similar to the past two times the US experienced similar downgrades in 2011 and 2023, with five-year CDS levels approaching 50 bps.5 The pricing of default risk around 50 bps correlates closely to Moody’s Aa sovereign rating category probability of default of 0.592% over a five-year period.

Recent CDS pricing for the US implies the probability of default is much higher than its Aa-rated peers. It’s akin to countries in the lowest investment grade category of Baa, such as Italy and Greece, which have higher debt-to-GDP ratios of 137% and 142%, respectively, according to IMF estimates. Austria and Finland, which have the same Aa1 Moody’s rating as the US, have lower debt-to-GDP ratios at 83% and 86%, respectively. US CDS pricing is also much higher than Japan, which has the highest debt-to-GDP ratio among the G20 nations in 2025 at 237%.

Investors are also expressing increased US credit risk in the Treasury market, where the 10-year Treasury term premium has moved as much as 23 bps higher since the beginning of 2025. This is even higher than the 137 bps in October 2023, when long-term yields were under pressure due to analogous concerns over US debt levels and fiscal health.

Demand remains robust

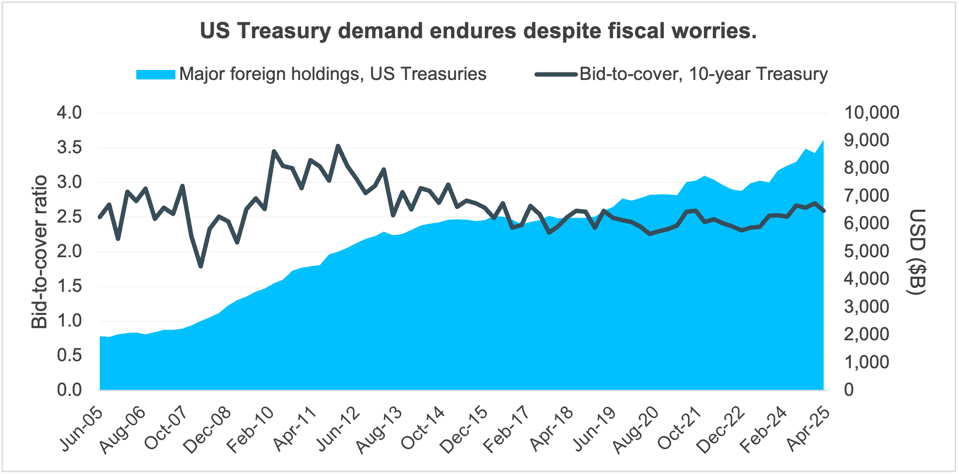

There are several ways investors can view the current situation. On the one hand, it’s indisputable that investors have priced in “higher” default risk, even if that likelihood still looks minuscule. On the other hand, the concern over US borrowing levels and fiscal health has not deterred buyers of its debt. Foreign holdings of Treasuries have continued to climb alongside issuance, with no material declines due to the loss of top credit ratings from the rating agencies. New issuance of Treasury debt has also not experienced any material decline in demand. The bid-to-cover ratio for 10-year Treasury auctions, as a proxy for demand, has been near the 2-year average of 2.6 over the past year. Since August 2023, when the US lost its second AAA rating, the average bid-to-cover ratio has been 2.54x, which is not materially different from its 20-year average.

We look for Treasury demand to remain steady despite the recent deterioration of credit fundamentals. Mounting interest expense, projections for annual budget deficits in the next few years and economic growth forecasted in the low single digits are likely to weaken the US fiscal position. Negative credit sentiment around Treasuries is further affected by political debate over the debt ceiling and the fact that such wrangling could cause a technical or temporary default.

Despite all this, we continue to view Treasuries as a risk-free asset. Here are five reasons investors should feel secure owning Treasuries:

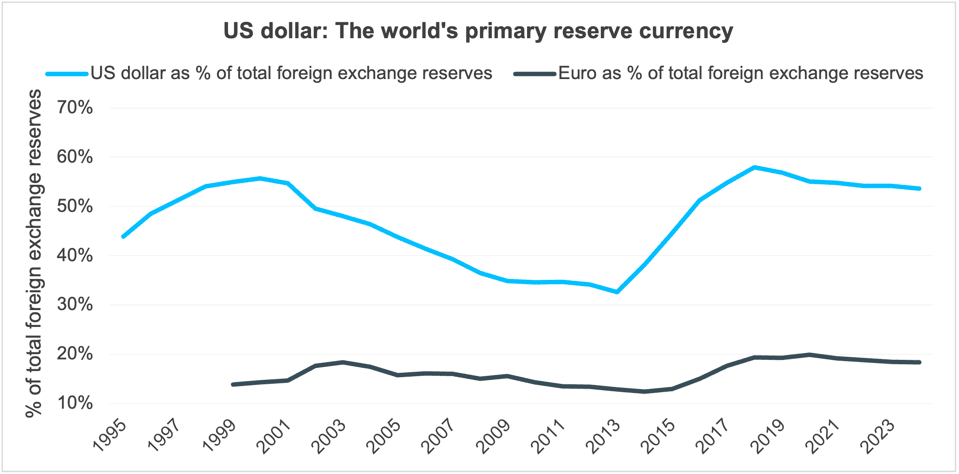

- The US dollar is king. The US borrows only in its own currency and has (for the moment) the unlimited capacity to make more US dollars to retire debt as it matures. The US dollar remains the world’s reserve currency. Despite currency alternatives such as the Euro, the US dollar still comprises 54% of total foreign exchange reserves as of 2024 and is nearly triple that of the euro reserves, which is the second-largest foreign exchange reserve.

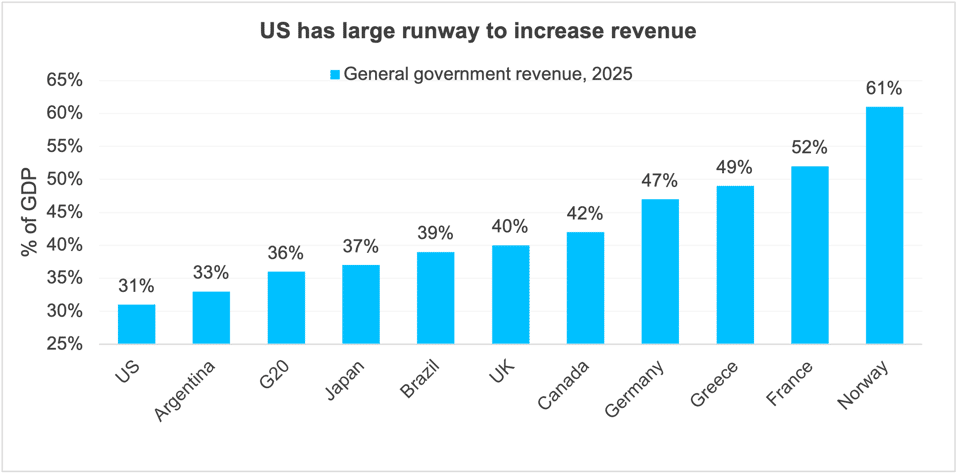

2. The US dollar is a revenue-generating machine. The US can increase revenue generation to slow the rise in debt levels and reduce debt outright. As a percentage of GDP, US general government revenue sits at a relatively low 31%, versus the average for G20 countries at 36%. It is nearly half of Norway’s 61% and 11% below Canada’s.

The political will to increase revenue to narrow the budget deficit or balance the budget is questionable, as any material increase in taxes is highly unlikely in the near term (though higher tariffs could boost receipts). Nonetheless, the mechanism to raise revenue does exist and is an available tool to generate dollars to repay debt.

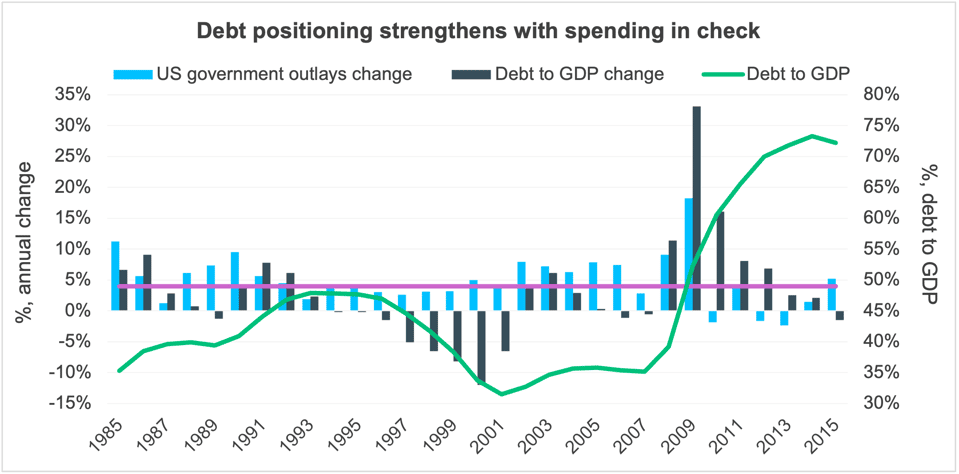

3. The US can constrain expenditures. Although it may be hard to remember, the US has demonstrated fiscal discipline in the past. Periods of annual expenditure growth below 4% have contributed to balanced budgets and led to reduced debt-to-GDP levels. For example, between 1993 and 2001, a time when the annual growth in government outlays averaged 3.4%, our debt-to-GDP fell from 48% to 32%. We also witnessed lower outlays for fiscal years 2012 and 2013. The political motivation to contain expenditures may be questionable; however, program changes and reductions can be implemented. It is possible.

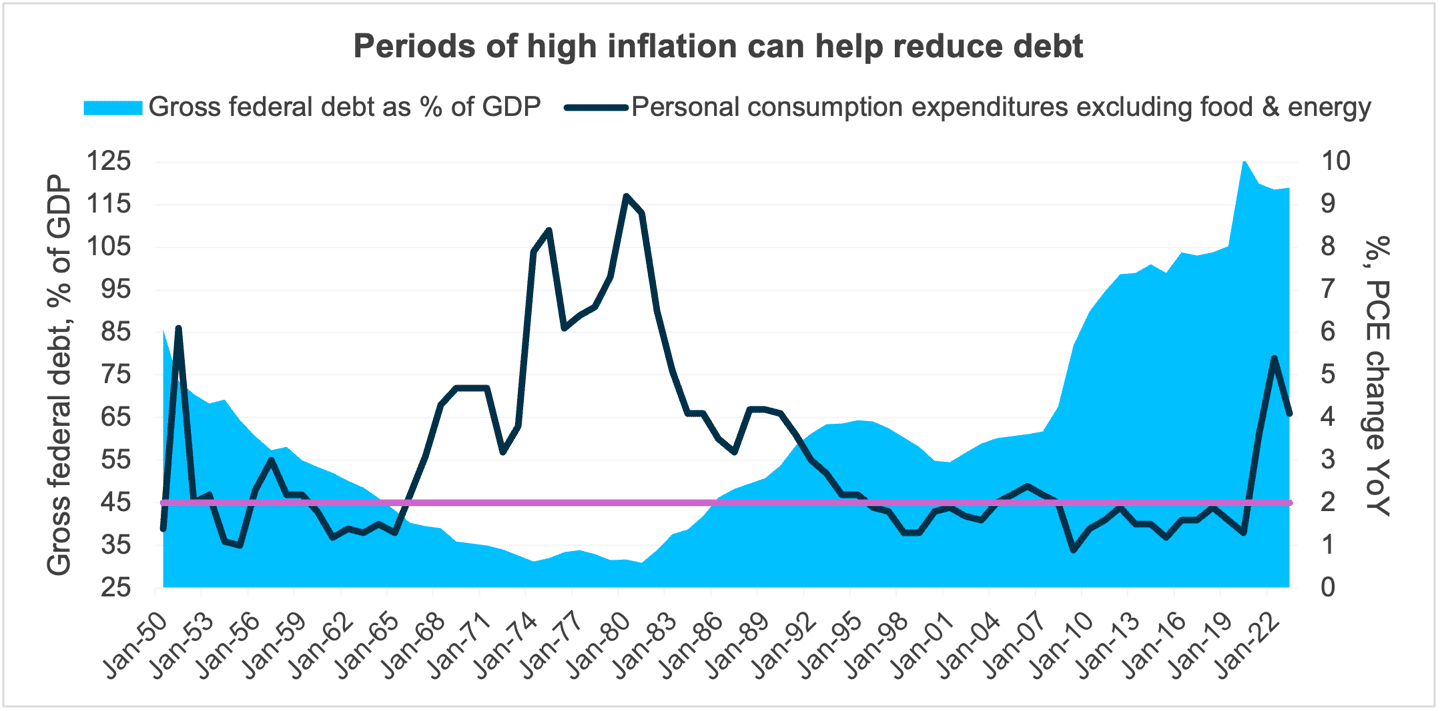

4. Inflation can lower debt. Periods of high inflation can have a silver lining. Put simply, inflation helps debtors, and that can include the US government. A period of elevated inflation from the early 1950s to the early 1980s contributed to debt deleveraging in the US. By comparison, a period of low inflation, such as the period after the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) from 2010 to 2020, increases debt leverage and is a headwind to debt servicing.

5. There is an iron-clad commitment. “The United States of America is never going to default. That is never going to happen.” This statement by US Secretary of the Treasury Scott Bessent in June 2025 is representative of our political leadership in the US, regardless of party. Amplified partisanship has indeed made fiscal policy more difficult in the recent decade, particularly when making changes to tax and budget policies. Even amidst the politics that have produced numerous theatrical threats of temporary or technical default, it has never happened.

So what’s the end game?

Rancor is commonplace in US politics, especially when it comes to our enormous budget. Recent unfettered spending does not seem wise or sustainable. And credit downgrades are certainly not to be celebrated. Nevertheless, the US continues to enjoy numerous benefits as the world’s largest economy, with the largest and most liquid sovereign bond market and the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency. Thus, Treasuries continue to have a role in virtually all fixed income portfolios, and the recent credit downgrade does not move the needle in terms of true credit default risk, in our opinion.

1 Source: USAspending.gov.

2 Source: Congressional Budget Office.

3 Source: Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

4 Free cash flow as percent of gross debt is US deficit as a percent of total federal securities borrowing from the public; EBITDA/interest expense is total receipts divided by net interest outlay.

5 A basis point (bp) is equal to 0.01%.