Key Takeaways

- Not every data point is a KPI. Focus on critical startup metrics that will really help you evaluate your business

- Every startup needs to understand its unit economics, customer acquisition cost, customer lifetime value and payback period

- Make realistic assumptions to estimate your total addressable market and work to understand your cost of growth

No matter what business you’re in, investors will expect you to be on top of certain metrics.

As you prepare to pitch investors, a good idea and even a good product are not likely to be enough. VCs will want to know whether you can turn that idea or product into a successful business.

To make that case successfully, you have to be able to tell a good and credible story about your business — one grounded in hard metrics. But figuring out which metrics matter most — the ones that can make or break your startup and that you can use as levers to control your business — is not necessarily easy.

We asked founders and VCs for what you should focus on. Here’s their advice.

After noticing how much his wife loved borrowing maternity clothes from friends during her pregnancy, Rakesh Tondon founded a fashion subscription service called Le Tote, where women could rent clothes. After bootstrapping the business for a few months in 2013, the former J.P. Morgan investment banker began a project to scrutinize Le Tote’s hazy future. He focused on identifying the “key performance indicators,” or KPIs, that would drive the company’s long-term success. The ultimate goal: to get a solid grip on the levers affecting his business and prepare to make a compelling pitch to investors.

With limited data of his own, this meant talking to other founders and his suppliers. He found out that volume discounts on shipping wouldn’t kick in until he passed 100,000 deliveries, but would quickly rise to 50 percent after that. Reaching that number would matter to his eventual profitability. Volume, however, would have little impact on the price of cardboard boxes, so that metric would not affect how he ran his business. Upon learning that the cost of clothing made by other brands also wouldn’t come down much with volume, Tondon decided to create his own private label. That way, he’d have more control over manufacturing costs and could make sure inventory was stacked toward the most profitable garments.

Tondon’s deep dive into the metrics driving Le Tote’s business allowed him to get a handle on the startup’s KPIs and paved the way for the company to hit its ambitious targets: gross margins have nearly doubled from 26 percent in 2015 to almost 50 percent in 2019. It was also critical as the company sought to raise venture funding at around the one-year mark. “Before we went to investors, we wanted to have a good sense of what the business would look like in 2015, 2017 and 2019,” Tondon says.

Investors liked what they saw. “We were impressed with how much they’d thought about the long-term drivers of their business,” says Michael Kwatinetz, a partner at Azure Capital Partners, who led Le Tote’s Series A round in February, 2015.

Top KPIs for any startup

The specific metrics that drive any business will differ from startup to startup, and very few first-time founders are likely to understand them from the get-go, says Efrat Kasznik, president of Foresight Valuation Group. But they must do the work to identify those inputs so they can calculate some basic KPIs that every founder should know.

Revenue, cost of goods sold and profit margins. During your company’s earliest days, you may not have built your product, much less know what customers might be willing to pay for it or how many units you’ll be able to sell. But it’s never too early to start thinking about these basic KPIs to understand whether your business will be viable. Estimating revenue — the price of what you sell multiplied by the number of units you expect to sell over a certain period — and the fixed and variable costs of generating that revenue is the starting point toward figuring out your expected profit margin. It will also help you approximate your burn rate — or cash flow, if you are actually able to bring in more than you spend.

Unit economics. Knowing the price and cost of what you sell, however, will only get you so far. To understand whether you have a shot at building a sustainable business, a key will be your unit economics. Whether you sell smartphones or monthly software subscriptions, this term refers to the profit you earn on each unit sold.

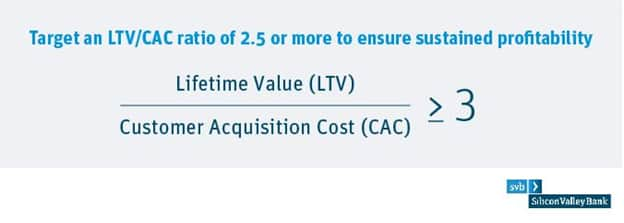

Figuring this out is always complex, but can generally be boiled down to a simple formula consisting of three critical KPIs. One is the lifetime value of a customer (LTV), or the amount the average customer will spend with you over time. To determine LTV, you must divide the average spend of a customer over some time (month, quarter or year) by your churn rate, or how frequently customers stop buying from you. Next, dividing the LTV by the customer acquisition cost (CAC) — the amount you spend on marketing, promotions and incentives to win a new customer — provides you unit economics and a basic outlook on profitability.

There is no single answer for what values these KPIs should have to prove your business is viable. But a rule of thumb is that if your LTV divided by your CAC is less than three, the business may not be worth pursuing because it may take too long for the company to become cash flow positive. Also, investors get nervous if the payback period, or the time it takes to recoup the CAC, is more than 12 months.

Only by knowing a startup’s unit economics can its founder understand how long it will take the company to reach profitability — and can investors know if they want to provide enough funding for it to survive that long. “The long-term survival of your company depends on it,” says Kasznik.

Total addressable market. VCs follow a swing-for-the-fences model: It’s ok for them to miss (lose their investments on startups that fail) if their hits are big. That means they’re going to want to make sure the market your startup is going after is large enough to be worth their time and dollars.

There are two main ways to estimate your total addressable market: top down and bottom up. In the former, you use industry data to put contours on what you’re going after — say, urban transportation, productivity software or online groceries — and adjust that by the percentage of the market you can realistically aspire to capture. In the bottom-up approach, you make estimates of how many products you can build and sell, based on things like your capacity to deliver and your distribution strategy.

It’s important to be both realistic about these projections and understand your audience. In Silicon Valley or New York, many VCs will nod off if you say your total addressable market is less than $1 billion. On the other hand, if you are building a product or service for the domestic market in Australia or the United Kingdom, the same claim could get you laughed out of the room. Similarly, if your business model rests on selling something to every school or hospital in the region you are targeting, you’re not likely to get the funding or valuation you want. In other words, it’s okay not to be sure about your numbers, but you have to tell a believable story.

Cost of growth. As they project into the future, many first-time founders fail to factor in the costs they will need to incur to support growth, says Kasznik. That includes not just the advantages of growth — such as those volume discounts that Tondon discovered — but by far the biggest cost for most tech startups: employees. Median annual salaries for IT professionals can be steep — $82,000 in Austin, $94,000 in Boston, $103,000 in Washington, D.C. and $110,000 or more in Seattle or San Francisco, for example — not counting benefits. Even in lower-cost locations, payroll frequently exceeds 60 percent of a startup’s costs.

The goal of KPIs is understanding, not data

Of course, there are many other detailed metrics that you’ll have to understand to optimize your startup’s performance. But don’t confuse detailed record-keeping with true understanding, says Kwatinetz. Too often, he’s had first-time founders present 100-line spreadsheets to him, with line items for predicted monthly expenses plotted out for the next three years for everything from phone bills to health insurance expenses.

The takeaway

If you want to understand — and be able to explain — your business, you must identify and focus on the few critical numbers that really matter to its trajectory. Investors will want to know what they are, and they’ll want to make sure you have a solid grasp of their effect on your business. “If you give me this information, I’ll be closer on your operating costs in three years than you will,” Kwatinetz says.

It’s likely that as a first-time founder you won’t have an innate understanding of all the levers affecting your business. That’s okay, says Kwatinetz. “I’ve known many successful first-time founders who didn’t. But they had to be willing to learn.”

Running a startup is hard. Visit our Startup Insights for more on what you need to know at different stages of your startup’s early life.