We’re pleased to provide you with insights like these from Boston Private. Boston Private is now an SVB company. Together we’re well positioned to offer you the service, understanding, guidance and solutions to help you discover opportunities and build wealth – now and in the future.

Tips for including Antiques, Art, and Collectibles in your financial and estate plans

We've all heard the remarkable tales about people who stumbled on antiques or works of art worth millions of dollars in their attic or at yard sales. But even those of us who have artwork or collectibles in full view in our homes may not know how much they are actually worth.

For example, take the Massachusetts couple who decided to sell some of their Victorian furniture to raise cash for and extensive home renovation - and in the process discovered that the old family painting in their living room was worth millions.

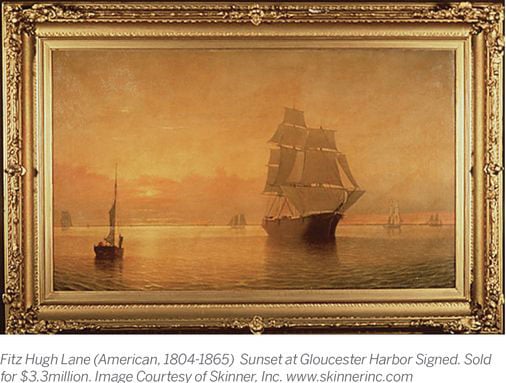

It's a story that Karen Keane, CEO of Skinner Auctions, remembers well. "When a smaller auction house came in to look at the furniture, they offered to buy a painting hanging over the mantle for $5,000 right on the spot," Keane recalls. The speed of the offer surprised the couple, she says, because that seemed like a lot of money for a picture that had been in the family forever and that they knew little about.

Wisely, the couple called Skinner for a second opinion. "It turned out that this painting was a rare Fitz Henry Lane painting from the pre-Civil War Cape Ann School. Lane is known for his marine scenes with beautiful pink skies, and he's part of a group of painters called the Luminous School," Keane explains.

"When we eventually offered the painting for auction, it went for $3 million."

While such finds are relatively rare, what is far less rare are those who avidly collect artwork, antique furniture or glass, cars, coins, stamps, perhaps comic books or vintage toys. Recent figures suggest that high net worth households worldwide have an average of 9.6% of their worth in collectibles.1

The role of personal property in your portfolio

Whether you're a dedicated collector, or someone who has periodically purchased (or inherited) art, antiques, or other collectibles over the years, where does this type of tangible property fit into your financial estate planning?

Most financial planners suggest thinking about these assets as alternative investments because - unlike stocks, bonds, real estate, or cash - most of these items (with the exception of gold, silver, and certain gemstones) have no intrinsic value, and typically valuation has no direct correlation to the performance of financial markets.

They are also investments with no certainty of a high return. For every Honus Wagner baseball card that netted its owner a cool two million dollars, there's a cherubic Hummel figurine sadly languishing on eBay.

What a piece of art or a vintage car or any other valuable collectible is worth today is based on how experts view their rarity, uniqueness, or desirability. Some items are considered valuable antiques due to their age (typically 100 years old or more), provenance, and condition. Others carry a high price tag because of their current popularity or nostalgic value.

Some collectibles may never increase in value. Pre-made collections of coins, like Franklin Mint are sold in such large quantities that they will not be rare for many years, if at all, says Keane. "They are sold with the claim that they will increase in value, and they typically never do," she says.

Pros and cons of investing in art, antiques and other collectibles

Even if an object was once highly prized, its value when sold depends on the whims of potential buyers and the trend of the times. Making money by investing in art, antiques, and collectibles is hardly a sure thing.

"Right now, for example, the market for very high end antiques and collectibles remains strong," Keane says. This past summer, the Wall Street Journal reported that collectors who were worried about last year's economic and political turmoil started returning into the big auction houses, where they were competing with an influx of new, wealthy buyers from china with extra money to invest. According to the Journal, Christie's auction house saw a 29% increase in the number of collectors who paid seven figures or more for a single work of art, as "new buyers are muscling swiftly toward the upper reaches of the market."2

"But when you come down a notch to items in the middle range and lower end of the market, that part of the market has struggled since 2009 - and continues to do so," says Keane. "So a block front desk made in SVB in the late 18th century, which might have been a $75,000 item ten years ago is now a $30,000 item. The entire market has softened."

And, more often than not, what these collectors will take away from their investment - after deducting the cost of taxes, insurance, storage, and maintenance - is far less than they imagined. "That's why it pays to be cautious whether you're buying or selling."

That's also why, for most of us, the primary reason to buy or keep an expensive work of art or collectible should be the emotional satisfaction that comes with its ownership - and not the possibility of making money from its sale. "We always say 'Buy what you like'," Keane emphasizes.

Think before you leap

Keane offers the following suggestions for anyone buying, selling, or just holding on to antiques, collectibles, and other tangible personal property.

When you buy an antique or collectible, think about not only the initial cost, but also the cost of care and maintenance, storage, and insurance. You'll also want to do some research using the online sites of reputable appraisal firms to compare your purchase to similar items and make sure the one you're looking at is fairly priced and authentic. You don't want to know that you're not overpaying or being duped by a counterfeit.

When you sell an item you've collected, remember the lesson from the Fitz Hugh Lane panting story: Do your homework and get expert guidance. "You want to be careful when someone immediately offers you a number that sounds like a lot of money." Be cautious when you sell things outright until you've heard some opinions on them," says Keane.

Remember too that an antique dealer's goal is no different than that of most other investors: buy low, and sell high. "The antiques business is full of folks who are trying to buy things for the least amount possible and sell them for the most amount possible," she says. That's the nature of the business.

Also be prepared to wait longer to sell your treasure than you would for most liquid assets. It can take time to find a buyer for your specific item who is willing to pay the price you're asking.

If you decide to work with an antiques dealer to sell an item, the dealer can:

- buy your item outright at a mutually agreed-upon price

- take it on consignment

- sell it at auction

If you choose the consignment or auction route, you'll typically pay a fee for those services, including preparation, display, storage, and advertising. And it will be up to you to pay capital gains taxes on any money you make on the sale.

Keane is a huge proponent of using auction and consignments, which is why Skinner doesn't buy items outright. "That way we are working in concert with families, in their best interest. When we sell things on consignment, for a commission, and they do well - we do well."

She also likes the auction process because it's transparent and gives you a fair market value for your piece. "When somebody buys something outright for, say $5,000, and then sells it privately, you have no idea what the item ultimately sold for."

She believes consignment or auction are also the best methods for individuals who want to sell an item they've inherited and don't know what it's really worth. In that case, "it's probably not a good idea to go into the marketplace solo. You should be dealing with someone you know and trust who can give you an opinion on a piece."

If you hold on to an item and don't intend to sell it, it's still important to know its value for insurance, tax, and estate planning purposes.

But how can you be sure you're getting an accurate appraisal from a Qualified Appraiser? Keane has these suggestions:

- Make sure the appraiser is certified through U.S.P.A.P. (Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice).

- Ask about appraisal fees and confirm that the fees are based on a flat or hourly rate, independent of the value or quantity of items being examined.

- Let the appraiser know why you need a formal appraisal. Is it for insurance coverage, estate tax filing, estate planning (and equitable division among family members), estate settlement (probate), or a charitable contribution?

This final point is important because the appraiser may use a different valuation method based on how the number will be used. Insurance appraisals are typically based on an item's replacement value, or what it will cost to replace a piece of personal property. On the other hand, if you need the information for estate planning, you'll want to know its fair market value (FMV) or current selling price. That is, if you had to liquidate the item today, what would it bring from a sale between a willing buyer and a willing seller.

Remember too that the FMV estimate you'll get from an experienced appraiser is based on what the item might fetch on the open market today from a buyer who is reasonably disposed to purchasing it. It will not take into account any emotional value you may have given the item.

It is also important to factor in prospective tax implications of keeping items to be conveyed at your passing or gifting them during your lifetime. There are various considerations to take into account regarding your lifetime gift exemptions and step-up in cost basis, to name a few.

How to include your wishes for personal property in your estate plan

Once you've received fair market value (FMV) appraisals for your most important antiques and collectibles, how do you incorporate this information into your estate plan?

- To bequeath family heirlooms and collectibles that have more sentimental and emotional value than intrinsic value to specific family members, simply include them in a non-binding memorandum to the personal representative for your will or the trustee of your trust. The memo should specify what items go to which people. (If no memo is available at your death, then your personal representative or trustee can make distributions at his or her own discretion, which may not be what you intended.)

- Larger items with greater value should be treated as specific gifts or bequests within your will or trust document.

- To prevent family arguments about who gets what later on, you also can make gifts of specific items during your lifetime or include “binding” specific bequests at death.

- Finally, you can donate any property of value to charity through lifetime and/or testamentary gifts that potentially provide a charitable deduction.

How SVB Private can help

As you make decisions about the future of your tangible personal property your SVB Private advisor can work with you to locate the expert resources you need. He or she can help connect you with independent firms that specialize in appraisals and provide advice on the acquisition or sale of fine art, antiques, collectibles, and jewelry.

In addition, your advisor can work with you to identify what, if any, updates are necessary to your estate plan and trust documents to include direction on the disposition of the personal property items you intend to pass on to future generations.

1 According to a Barclay’s 2012 report as quoted in Forbes

2 https://www.wsj.com/articles/newcomers-muscle-into-art-markets-high-end-1500440400

WSJ article – 7/19/17