Since the 2017 tax reform law was enacted, many investors and entrepreneurs considered the personal wealth implications around the loss of state and local tax deductions (SALT). At the root of it, this tax reform limited the SALT deduction to $10,000 – which particularly impacted high-earners in high-tax states whose SALT bills typically far exceed $10,000.

With these laws in place, coupled with the fluid work environment brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic, many high-earners have considered the advantages of moving to greener financial pastures. To help you determine if a similar move is financially advantageous, we’ll examine the factors involved when considering relocating for tax purposes.

With more organizations offering flexible work arrangements and creative compensation packages, you may be wondering if your employer can be based out of one state while you perform your employment duties from your domicile in another state. As always, any solid wealth protection strategy should weigh potential tax advantages with your estate planning goals and quality-of-life considerations. In addition, your domicile has significant legal implications that should be discussed with your attorney during the planning stages.

To help, we will explore the state tax implications of claiming a domicile vs. part-time residence, collecting equity and deferred compensation and changing family status and estate planning. As always, you should consult with a tax advisor regarding your unique situation.

Proving a domicile vs. a part-time residence

You may have more than one residence, however, for tax purposes, you are only allowed a single domicile. In simple terms, your domicile state is defined as the location that you call home and the place where you always intend to return.

Of course, moving your family involves many considerations in addition to taxes; a change of domicile likely will mean a profound shift for you and the people in your life.

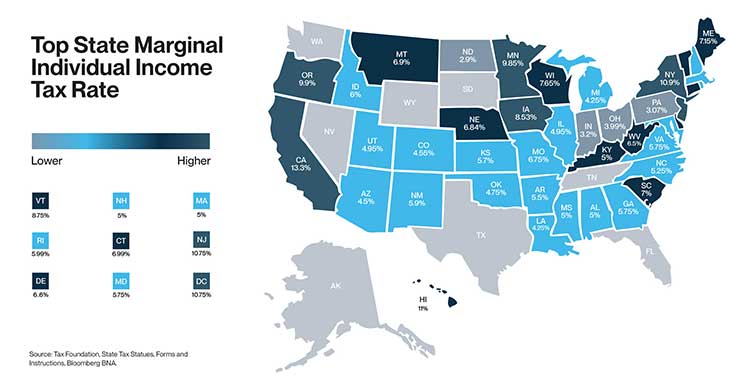

If taxes were the only consideration, you may not think twice about leaving California, with its state income tax rate of 13.3%, and decamping to Alaska, with no state income or estate tax and robust asset protection laws.

Looking past a six-month stay

States generally use a “six-month presumption”, declaring that living in a state for six months (183 days) per year qualifies you as a domiciled resident. However, simply residing outside a high-tax state for 183 days per year is not enough to gain a tax advantage. Other domiciled residency criteria must be acknowledged, which if unsatisfied, could jeopardize your low-tax residency strategy and weaken your position during a state tax authority residency audit, possibly causing you to lose the audit.

For example, if a state finds you have made significant taxable income, have meaningful contacts, such as a second home, material business interests and/or visit the state for extended periods, you may face a protracted, heavily contested residency audit.

Residency audit factors

There are several factors that may lead to a residency audit. Learning criteria involved can help you understand the scope of changes required to properly change your domicile in the eyes of the state, such as:

- The amount of time you spend in your state versus amount of time you spend outside your state

- The location of your spouse/registered domestic partner and children

- The location of your principal residence

- The state that issued your driver’s license

For a more detailed list of factors involved in determining your residency status, review our Change of Residency Checklist. It is critical to note that failure to meet state residency requirements may negate the tax benefits you hope to achieve and result in orders to pay back taxes that include penalties.

Understanding how state income taxes are applied

State income tax filings may consist of: (1) the primary state tax by your domiciled state, (2) any secondary income tax for any part-time residency state and filing with that respective part-time state and (3) credits your domiciled state will give for the payment of the secondary tax. Primary residents are taxed by their domicile state (unless the state has no income tax) on all income, including income from sources outside of their domicile state.

Generally, when living in and earning income in another state, that state taxes only what was earned during the part-time residency. However, some domicile states give you a credit for income taxes paid on earnings made in another state. For example, if you’re domiciled in New York but moved for a period to Massachusetts to work for a local company, you would pay income tax to Massachusetts only on the earnings from Massachusetts and on all earnings to New York.

Unpacking potential implications with equity and deferred compensation

Under the current tax rules, even though you may participate in a deferred compensation program sourced in one state and then move to a lower-tax state, the deferred compensation would be taxed by the previous state. However, if you elect to take the deferred compensation payments over a period of more than 10 years, the tax on the deferred compensation payments is set at the rate applied by your domicile state when you receive the payments.

For example, if you participated in a deferred compensation program such as a pension or nonqualified plan in Massachusetts and then made Florida, which has no income tax, your new domicile, all the deferred income you collect in Florida will be taxed by Massachusetts at its 5.0% income tax rate (unless the payments are spread over more than 10 years).

If you have incentive stock options (ISOs), non-qualified stock options (NSOs) or restricted stock units (RSUs), the taxes are applied based on where the shares vested, not where they were granted. For example, if you had 100,000 RSUs and 80,000 of them vested before you moved from California to Massachusetts, then, the 80,000 would be taxed by California. The remaining unvested RSUs would be considered earned in Massachusetts.

The RSU example above applies the most common interpretation of a “reasonable method” to allocate equity compensation income between two states. Other reasonable methods exist and may apply depending on the particulars of your circumstances.

Understanding how state family law varies

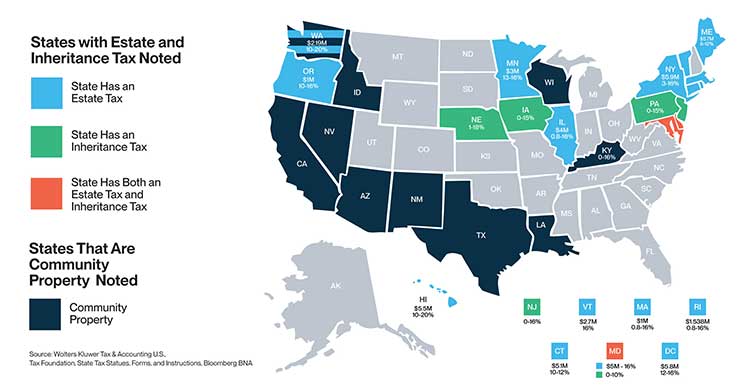

In community property states, marital property is defined as property owned by both spouses equally (50/50) and includes earnings, purchases made with those earnings and debts accrued during the marriage. Community property states also consider assets owned before marriage as separate property. It may seem that keeping “separate property” and “community property” straight is easy, but then consider the consequences of filing separate or joint state/federal tax returns. Consider how to use “community income” to pay the mortgage on one’s “separate property”? The process can be difficult.

Marital assets following a divorce, legal separation or death are divvied up differently depending on whether you live in a common law property state or a community property state. If you are changing your marital status, it’s prudent to consult a state-specific family law attorney and tax advisor to fully understand the process.

Some states also have specific exclusion amounts and exemption rates for estate and/or inheritance tax that differ from the federal lifetime exclusion rate. This may have an impact on language in an existing estate plan. State legislation may change often. The individual federal lifetime exemption became $12.06 million in 2022.

Depending on your situation, change of domicile may not be necessary or beneficial. Other solutions that may be more effective include the establishment of a trust or LLC in a more tax-advantaged state. Ultimately, estate and trust documentation will need to be redrafted by an attorney practicing in the new state to adhere to that state’s laws.

Plan a tax strategy with a team of experts at your side

Planning a tax-efficient strategy and implementing it will take time. Contact your SVB Advisor to get started. As your primary contact, your Advisor can help guide and connect you with other professionals, and we recommend that you seek counsel from your tax and estate plan professionals, to work with us to design the best wealth strategy for you.